Achilles Tendon Acute Rupture

Introduction

- common injury

- male to female ratio of 5:1

- affects athletes and middle-age populations

Presentation

- acute pain

- 'pop' may be felt or heard

- often described as if being kicked or shot

- difficulty in walking or bearing weight due to failed mechanics

- follows sudden acceleration activity e.g. playing racquet sports, running for a bus

- usually a non-contact injury

History and Examination

Thorough history and examination are required to differentiate from:

- deep vein thrombosis

- stress fracture

- claudication

Clinical tests include Simmonds' triad:

- calf squeeze

- altered angle of declination

- palpable gap

The combination of all three signs confirms the injury in most cases.

Figure 1: Left acute Achilles tendon rupture - note visible gap with loss of tendon continuity

Figure 2: Left Achilles tendon rupture showing change in 'angle of dangle'

Imaging

- x-rays to exclude bony avulsion or calcaneal fracture

- ultrasound may be useful to identify:

- if the rupture is mid-substance or at the myotendinous junction

- partial or complete

- gap size and if reduces with plantar flexion

Aetiology

Multifactorial; risk factors include:

- increased physical activity

- quinolones e.g. ciprofloxacin

- corticosteroids

- increasing age

- male gender

- (pre-existing tendinopathy)

Management

Initial management involves:

- immobilisation in a back/frontslab plaster

- analgesia

- DVT prophylaxis

Shared decision-making should then determine ongoing management:

- non-operative (conservative)

- open repair

- mini-open / percutaneous repair

Historically, studies have shown:

- higher re-rupture rate with non-operative management (but lengthy immobilisation)

- higher complication rate with surgery (infection, wound breakdown)

Recently, studies have shown:

- no or minimal difference in re-rupture rate when functional rehabilitation is used for non-operative management

- possible increased muscle strength post surgery (but higher complication rate)

- otherwise, no difference in long-term outcomes

Conservative

Functional rehabilitation has gained popularity in the UK:

Most units now have a rehab programme similar to this:

- 2 weeks in cast in full plantar flexion, NWB (consider DVT prophylaxis)

- Commence WB in range-of-motion walker boot in full plantar flexion

- Reduce plantar flexion by 15 degrees every 2 weeks

- Final 2 weeks in boot in plantigrade position

- Heel raises in trainers for 4 weeks

- Physio rehab

Early tendon loading encourages earlier collagen maturation and fibre orientation (animal studies).

There is increasing evidence that use of ultrasound and the tendon 'gap' are not helpful in management.

Operative

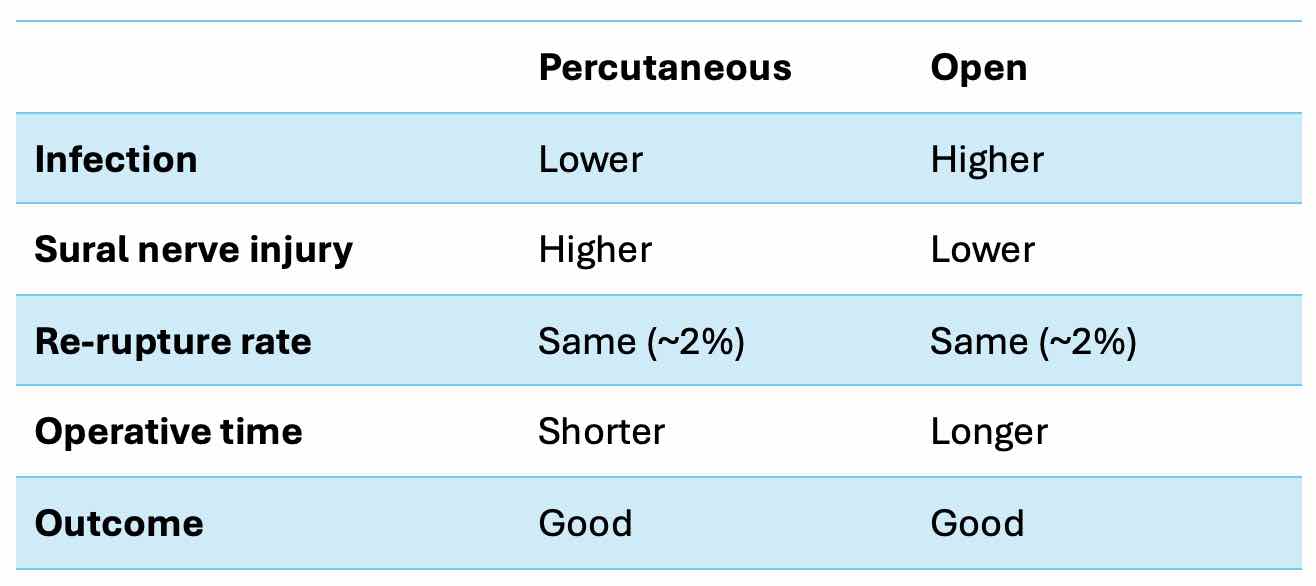

Table 1: Pros and cons of Percutaneous vs Open repair

Rehabilitation

It is generally accepted that rehab and recovery is the same for operative and non-operative management.

Outcomes are generally excellent, with most patients returning to sport and full function.

References

Fan L, Hu Y, Zhou L, Fu W. Surgical vs. nonoperative treatment for acute Achilles' tendon rupture: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Surg. 2024 Nov 21;11:1483584. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2024.1483584. PMID: 39640199; PMCID: PMC11617549.

Saxena A, Giai Via A, Grävare Silbernagel K, Walther M, Anderson R, Gerdesmeyer L, Maffulli N. Current Consensus for Rehabilitation Protocols of the Surgically Repaired Acute Mid-Substance Achilles Rupture: A Systematic Review and Recommendations From the "GAIT" Study Group. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2022 Jul-Aug;61(4):855-861. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2021.12.008. Epub 2021 Dec 10. PMID: 35120805.

Liu X, Dai T, Li B, Li C, Zheng Z, Liu Y. Early functional rehabilitation compared with traditional immobilization for acute Achilles tendon ruptures. Bone Joint J. 2021;103-B(6):1021-1030. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.103B6.BJJ-2020-1890.R1

Matthew L Costa, Juul Achten, Ioana R Marian, Susan J Dutton, Sarah E Lamb, Benjamin Ollivere, Mandy Maredza, Stavros Petrou, Rebecca S Kearney, UKSTAR trial collaborators; Plaster cast versus functional brace for non-surgical treatment of Achilles tendon rupture (UKSTAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation; Lancet. 2020 Feb 8;395(10222):441-448. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32942-3.

Yang B, Liu Y, Kan S, Zhang D, Xu H, Liu F, Ning G, Feng S. Outcomes and complications of percutaneous versus open repair of acute Achilles tendon rupture: A meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2017 Apr;40:178-186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.03.021. Epub 2017 Mar 11. PMID: 28288878.

Deng S, Sun Z, Zhang C, Chen G, Li J. Surgical Treatment Versus Conservative Management for Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017 Nov-Dec;56(6):1236-1243. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.05.036. PMID: 29079238.

Lantto I, Heikkinen J, Flinkkila T, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing surgical and nonsurgical treatments of acute Achilles tendon ruptures. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(9):2406–2414. doi: 10.1177/0363546516651060.

B.J. Erickson,R Mascarenhas, B.M. Saltzman, D. Walton, S. Lee, B.J. Cole,B.R. Bach; Is Operative Treatment of Achilles Tendon Ruptures Superior to Nonoperative Treatment? The Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 2015 3(4), 2325967115579188; DOI: 10.1177/2325967115579188.

Soroceanu A, Sidhwa F, Aarabi S, Kaufman A, Glazebrook M. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40 (9): 2154-2160.

Costa ML, MacMillan K, Halliday D, et al. Randomised controlled trials of immediate weight-bearing mobilisation for rupture of the tendo Achilles. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:69-77.